The American Hospital Association is urging the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission to abandon a Medicare Part B drug reimbursement policy option it is considering making to Congress, arguing that the proposed change would hurt 340B hospitals’ ability to provide care by reducing their 340B savings.

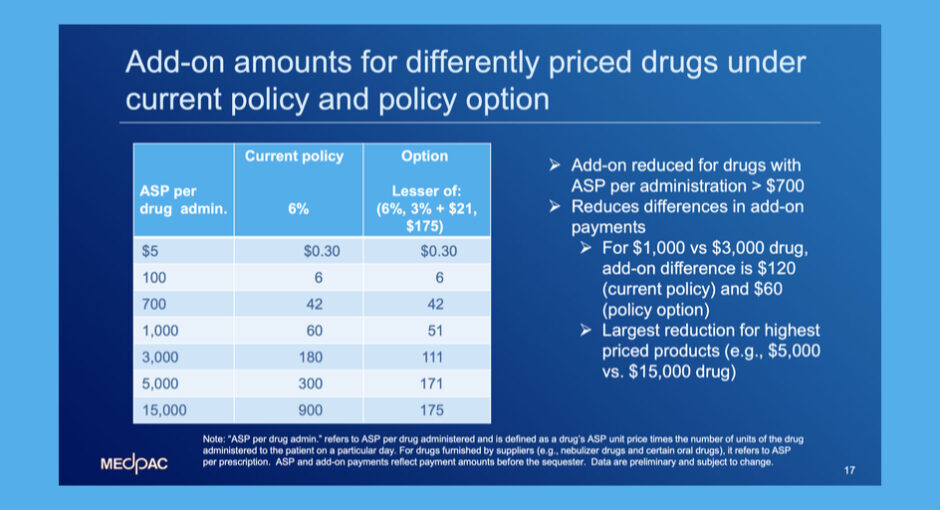

As MedPAC’s September meeting, its staff briefed commissioners about ways that Medicare could address the high price of drugs covered under Part B, including converting the 6% add-on to Part B drug reimbursement to a fixed fee capped at $175 for drugs that cost $15,000 or more, phased in starting with drugs costing above $700.

MedPAC staff said the new formula, which would apply to 340B and non-340B hospitals, would reduce Part B drug payments overall by 2.6%.

The discussion came just two weeks after a federal judge in Washington, D.C., ordered the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to immediately resume paying hospitals for 340B-purchased Part B drugs at ASP plus 6% after paying them at an illegal ASP minus 22.5% rate since 2018.

In a Sept. 26 letter, AHA asked MedPAC to support the re-established ASP plus 6% methodology.

“While we recognize MedPAC has raised concerns regarding 340B, we continue to respectfully disagree and note that some of the proposals would further exacerbate the health care system’s ability to care for some of our most vulnerable communities,” AHA told the commission. “For the over 2,000 hospitals around the country that participate in the 340B drug pricing program, the impact could be particularly severe and problematic.”

Cutting 340B hospitals’ Part B payments would cut the 340B savings they use to pay for critical programs and services for low-income patients, AHA said. It also would shift responsibility for drug price increases

to hospitals and patients and away from drug manufacturers, it said.

AHA also cast doubt on the view that the ASP plus 6% model encourages providers’ use of the highest priced drugs in order to get the fattest reimbursements, an argument that has particularly angered 340B providers.

“There is no convincing evidence that hospitals and clinicians consider profitability over clinical effectiveness when deciding which drugs to use,” AHA said. “Drugs are purchased by hospitals and prescribed by physicians based on clinical considerations; the chosen drugs are determined to be the most effective in treating the individual patients for whom hospitals and clinicians care, while minimizing side effects and dangerous drug interactions.”

AHA also argued that it would be premature to reduce Part B payments before the impact of the Inflation Reduction Act is fully understood.

“The IRA requires that Medicare negotiate the price of a certain number of drugs annually and requires these selected drugs be made available to Medicare Part B providers and suppliers at no more than the

negotiated rate of maximum fair prices (MFP), with Medicare payment for the selected drugs set at the reduced rate of MFP plus 6%,” AHA said. “To the extent that providers depend on the add-on amount to help cover pharmacy overhead costs, such as drug storage and handling costs, or to supplement Medicare underpayment for other services, this double reduction could be problematic.”