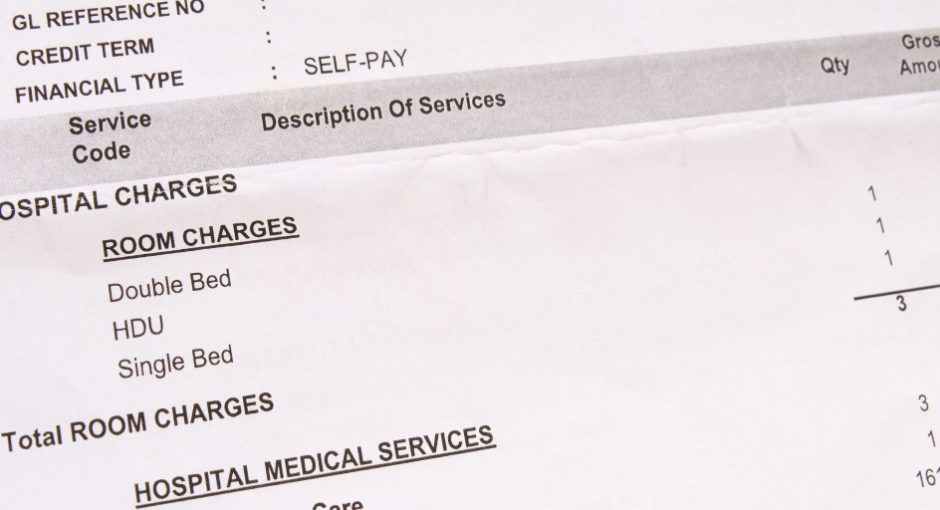

Many 340B hospitals “may not offer low-income patients financial assistance to access medicines and may use extraordinary collection actions, including but not limited to, liens, foreclosures, and civil actions when patients fail to pay bills,” a pharmaceutical-industry funded study released yesterday concludes.

Bharath Krishnamurthy, American Hospital Association (AHA) Senior Associate Director of Policy, called the study “another example of PhRMA’s antipathy toward a program that serves vulnerable communities.”

The study was conducted by researchers at the Center for Public Health Law Research at Temple University’s Beasley School of Law. Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA) funded the project.

The Temple Law study evaluated financial assistance and debt collection policies at 75 of the largest 340B hospitals in the nation by revenue. It found:

- One hospital’s financial aid policy could not be located, six did not specify how they publicized their policies, and there was wide variation in how the others publicized theirs.

- Forty hospitals set their eligibility threshold for charity care at between 200% and 299% of federal poverty guidelines. Seven limited charity care to at or below 100%. Two set the eligibility threshold at above 500%. Four did not indicate their limit for free care and one did not have a policy, the study said.

- Thirty-seven hospitals required an asset test for financial aid, but an equal number did not. Thirty-five described their financial aid appeals process, but 39 did not. Twenty-three provided financial help for 12 months, while eight provided only three months of help.

- Six hospitals prohibited “extraordinary” debt collection actions such as legal actions, selling of debt, reporting to credit agencies, or “deferring, denying, or otherwise requiring payment before rendering of medically necessary care,” the study said. Forty-five hospitals required notice before commencing debt collection, but 19 did not. Thirty-nine specified no limits on collections.

- “Most hospitals in this sample did not clearly indicate pharmaceutical assistance available to patients in their [financial assistance plans] or how patients may receive discounts on needed medicines,” the study said. Thirteen provided such details. “Just one hospital specifically referenced 340B in detailing their own pharmaceutical assistance program,” the study found.

“The broad range of [financial assistance] policies in place at 340B hospitals suggests limitations in how the 340B program savings are used to help patients, specifically regarding affordability of medicines for low-income populations,” the study concluded.

AHA policy expert Krishnamurthy criticized the study’s narrow focus on 340B hospitals’ financial aid and debt collection practices.

“The provision of free care and financial assistance is just one of the many ways 340B hospitals reinvest 340B generated savings to help serve their communities,” he said. “In 2018 alone, 340B hospitals provided nearly $68 billion in benefits to the communities they served, which included the costs associated with underpayments from public payers and investing in critical programs and services such as medication therapy management, diabetes education, and mobile treatment clinics for underserved populations.”

340B Health, an association of 340B hospitals, declined to comment.