Democratic lawmakers have come to an agreement for placing a limited drug price negotiation plan for the Medicare program into the Build Back Better bill, but how it will impact the 340B program remains to be seen.

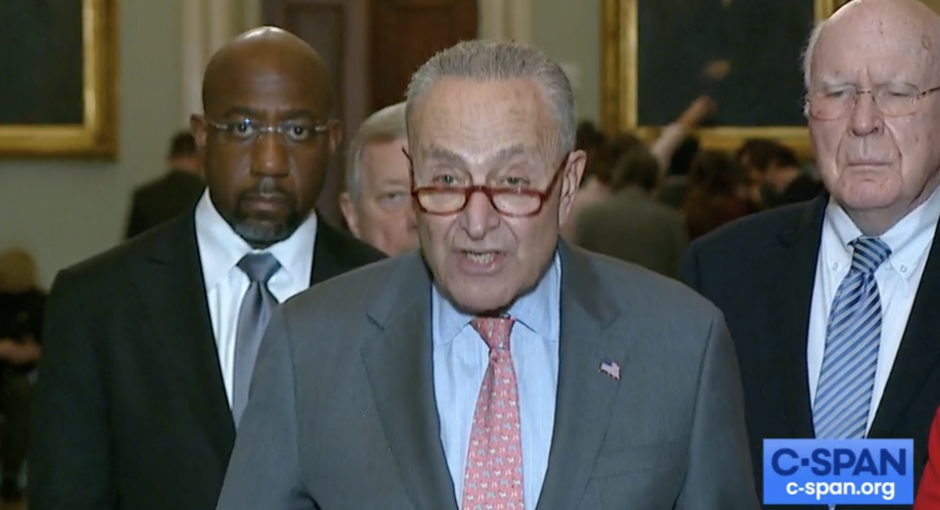

“By empowering Medicare to directly negotiate prices in Part B and Part D, this deal will directly reduce out-of-pocket drug spending for millions of patients every time they visit the pharmacy or doctor,” said Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.)

The Democrats’ broader agreement on drug pricing also would require manufacturers to pay the government rebates on certain drugs reimbursed by Medicare Parts B and D if a drug’s price rises faster than the rate of inflation. Some in the drug industry reportedly are pushing back against the prospect of being required to pay these new Part B and Part D drug inflation rebates on top of the existing additional Medicaid rebates they must pay and the corresponding additional 340B discounts they owe when their prices outpace inflation.

The framework for the plan, announced late Tuesday, includes the following, according to the White House:

- Drug price negotiations will begin in 2023 and take effect in 2025. They will be limited to up to 10 drugs in 2025, and 20 drugs in 2028 and beyond.

- The drugs limited to price negotiation are the highest-grossing single source drugs by revenue that are outside of their exclusivity period—nine years for small molecule drugs and 12 years for biologics. Insulin is also included on the list.

- Negotiated prices will be capped depending on the number of years that have passed since the drug’s initial exclusivity. They range from 75% of the non-federal average manufacturer price to 40%, depending on how many years have passed.

- Manufacturers will be required to submit specific information about any drug selected for price negotiation, including research and development costs, prior financial support from the federal government, the extent to which a drug addresses an unmet need, and whether it represents a therapeutic advance beyond existing treatments

- Manufacturers that refuse to negotiate on prices will be subject to an excise tax. However, any drug that contributes less than $200 million in annual Medicare spending is exempt from negotiation.

Additionally, the Part D program will be revised to cap out-of-pocket costs to $2,000 a year. Insulin co-payments will be capped at $35 a month—they have risen in some instances to $600 a month in recent years, even though insulin has been on the market for decades.

PBMs will also be required to report rebates to employers and plan sponsors.

“In the Build Back Better Act, Democrats will deliver strong drug price negotiations to lower prices for our seniors and halt big pharma’s outrageous price hikes above inflation, not just for seniors but for all Americans,” said House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.)

The pharmaceutical sector sharply criticized the plan.

“If passed, it will upend the same innovative ecosystem that brought us lifesaving vaccines and therapies to combat COVID-19,” said Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA) CEO and President Stephen Ubl. “Under the guise of ‘negotiation,’ it gives the government the power to dictate how much a medicine is worth and leaves many patients facing a future with less access to medicines and fewer new treatments.”

Ubl did praise the Part D cost caps, noting that “while we’re pleased to see changes to Medicare that cap what seniors pay out of pocket for prescription drugs, the proposal lets insurers and middlemen like PBMs off the hook when it comes to lowering costs for patients at the pharmacy counter. It threatens innovation and makes a broken health care system even worse.”

The Association for Accessible Medicines, which represents manufacturers of generics, also blasted the plan.

“Patient access to more affordable generic and biosimilar medicines would be threatened under the policies currently under consideration in Congress,” said AAM CEO and President Dan Leonard. “Competition from lower-cost generics and biosimilars has successfully led to decades of savings for patients. Continued access and savings to more affordable medicines would be jeopardized should these policies advance.”

Nonprofit group West Health, which works to lower health care costs for older people and includes Sean Dickson (a researcher who has conducted a number of 340B studies), called the agreement “a positive step forward” but said it “falls far short of the bold reform that is needed.”

“With razor thin margins in the House and Senate and a powerful pharmaceutical lobby that has a stronghold over Congress this is the best that could be achieved at this moment,” West Health President and CEO Shelley Lyford said. “However, our work is far from finished.”